Financial Statement: How to Read a Balance Sheet

Understand the basics of a Balance Sheet

In one of our articles, we wrote about how one can look into the annual report (or quarterly report) to pry into the financial well-being of a company. If you haven’t yet read our piece, you can find it here:

Fundamental Analysis: Invest Based on Annual Reports

Now, what you will learn from this article is on what are the information provided in a Profit & Loss statement. We will not yet delve into the methods that are used in churning all this information into a fundamental evaluation as that will require a much lengthier explanation and another article in itself.

Overview

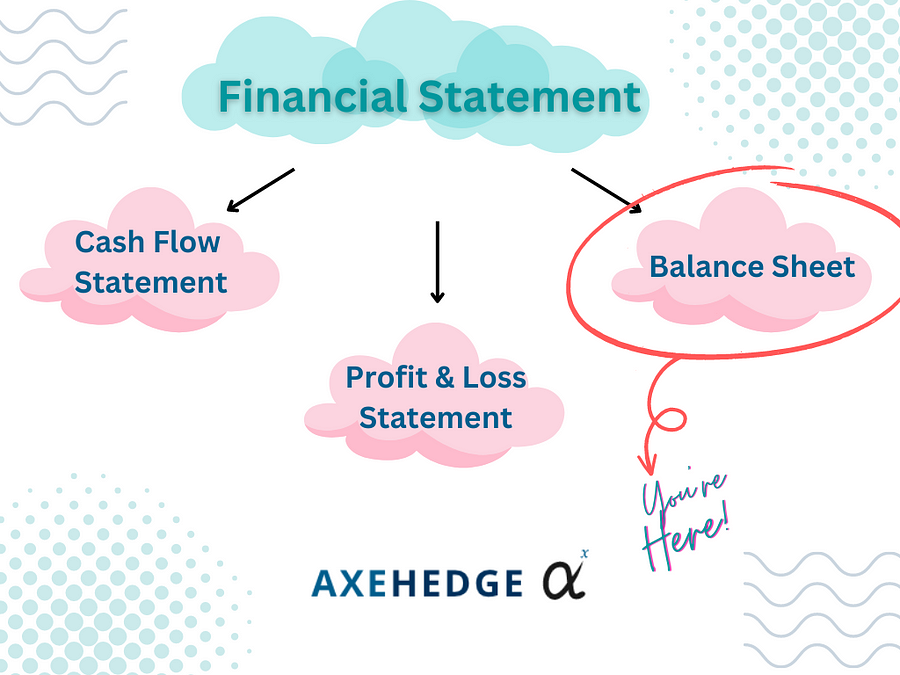

Before we proceed any further, we would like to give you a general overview of where we are.

In deciding which asset to buy, investors/traders often result to two main methods — fundamental analysis and technical analysis. Fundamental Analysis seeks to look for the actual value of a particular asset, not just look at the price that it’s listed at. Technical Analysis is more concerned with the market sentiment surrounding the asset rather than the asset itself.

One of the many things that a fundamental analyst would look into to understand the value of a company is the financial statements of a company. Under this financial statement label, there are generally three main documents that the analyst would look at: Profit & Loss Statement (P/L), Balance Sheet, and Cash Flow Statement.

Basic Knowledge:

Now, before we dwell any further, it is important for you to be aware of three things:

See the time of the publication: First, know when the report was published, and you’ll also have to know if it’s a quarterly report or an annual report. The way to do it is simply by looking at the title of the report, or the preamble. Knowing this is important because each timeframe will have its own gravity in the evaluation of a company.

Say, you want to invest in Company A for the span of just a year. In this case, it’s better if you look at its quarterly performance. It’s better if you can look at both, but your decision will rely heavily on either one of the two.

See the currency denomination: When the company presents its financial data, be sure to look at the currency denomination. We’ll explain it through the example below.

The currency denomination here is when it states “(dollars in millions)” which means that a single digit represented in the table equals a million, e.g., $1 = $1,000,000.

Yes, the things we mentioned above are perhaps really basics to many, but many of those who are just new to finance might not be aware of this.

A balance sheet is a flowing financial statement which means that it reflects the amount since the company was incorporated. The numbers were only added and subtracted either quarterly or annually. It’s almost like a perpetual stew.

(If you don’t know what a perpetual stew is, look it up — It would be worth it. Missed my bedtime going down the perpetual stew rabbit hole)

On another note, our examples here will be from Apple’s Q1’23 Financial Statements (the data is for Apple’s Q4’22 performance). You can download it here.

The cores of a Balance Sheet

Before we start, do know that sometimes the terms used are different from one company to another, but if you look at the data they present, you’ll know they are referring to the same thing.

Now, to Balance Sheet! There are generally two main parts of a Balance Sheet: assets and liabilities. From looking into these two parts, you can gauge how well is the company’s account doing. The end result is that you want to know how well the assets and liabilities of the company are balanced, and you want to know about the shareholders’ equity (which is directly mentioned in the Balance Sheet).

Asset

The first part of a balance sheet is the asset, which includes both tangible and intangible assets. Asset here refers to resources that has future economic value to the company, you will find that the categorization in a balance sheet is based on when will the asset materializes i.e., when will it actually be available Under this categorization, there are Current and Non-Current assets.

The formula for Asset:

Asset = Shareholders’ Equity + liability

Current

Current asset refers to the asset used to support the company’s day-to-day activities. This usually refers to assets that are utilizable within 12 months of the date from the time the balance sheet was prepared.

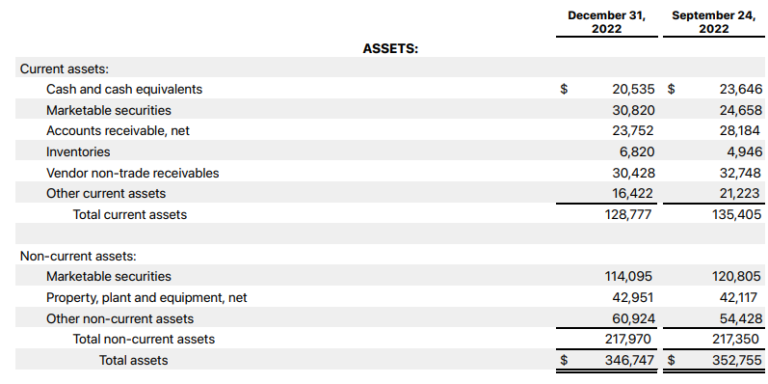

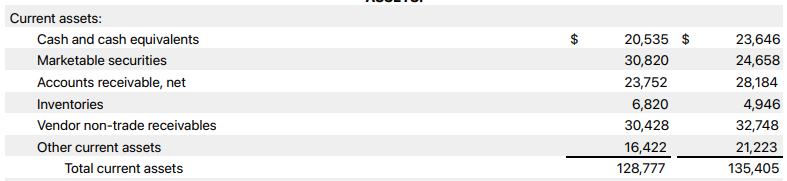

From the example above, we can see that the current asset includes a few things such as:

Cash and cash equivalents: Cash or anything that can be immediately converted to cash.

Marketable securities: Short-term liquid securities. You can find it at any public stock exchange or bond exchange. This asset can be liquidated quickly if you need cash.

Accounts receivable: Things that you’re entitled to receive within the short term. (If people pay in monthly installments, etc.)

Inventories: Inventories here are the things you have in your inventories that can be used for sales, and they can either be raw materials, work-in-progress, or finished goods.

Vendor non-trade receivables: This refers to the money that the company will get, but it’s not based on its business activity. For example, Apple sells iPhones and other products as well as services, but if Apple suddenly decides to give Company ABC a loan of $50,000 to be paid in less than a year, that $50,000 will be reflected here.

Other current assets: This is where other assets are mentioned, insofar as their materialization is less than a year.

Total: It tells you the total asset value. Usually, if you’re short on time, you can skip all the above and just look for its total value.

Non-current

Non-current asset refers to an asset that is considered a long-term investment and usually can’t be converted to cash within the same year. This usually refers to assets that are utilizable more than 12 months from the date from the time the balance sheet was prepared.

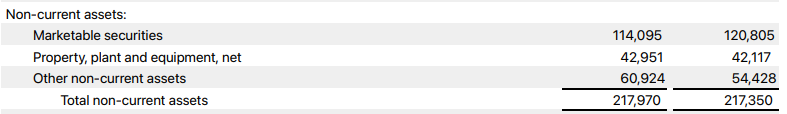

From the example above, we can see that non-current asset includes a few things such as:

Marketable securities: Same as above, but these are securities that the company doesn’t intend to sell within a year.

Property, plant, and equipment: Properties, plants, and equipment will bring benefits to the company within the same year, but they cannot be converted to cash easily.

Other: This is where other assets are mentioned, insofar as their materialization is not less than a year.

Total: It tells you how many non-current assets the company has in total. People would usually just jump straight to this part to save time.

Liabilities

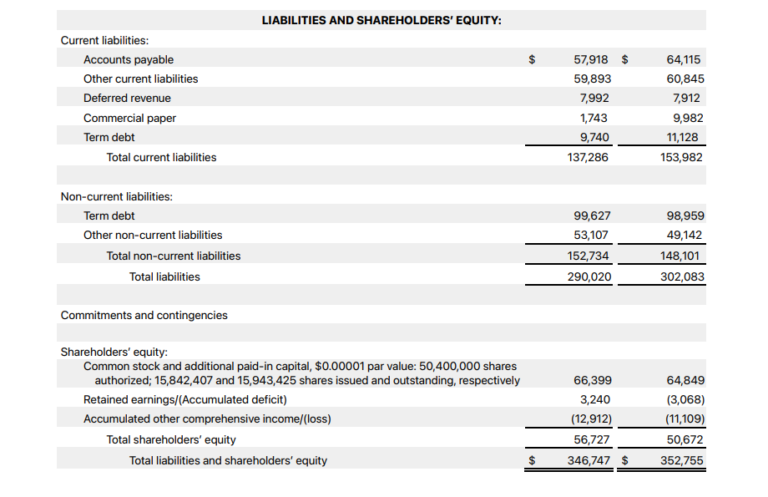

The second part of a balance sheet is the liabilities, which refers to the obligations that a company takes with them in the hope that it will bring economic value in the future. There are four main parts when speaking of liabilities: current, non-current, commitments & contingencies, and shareholders’ equity.

The formula for Liability

Liability = Current liability + Non-current liability + Shareholders’ equity

Current

Current liabilities refer to liabilities or obligations that the company will have to meet within 12 months of the date from the time the balance sheet was prepared.

From the example above, there are a few things mentioned under the current liabilities and they are:

Accounts payable: Accounts payable here refer to the amount that the company will have to pay be it to their vendors.

Other current liabilities: This is the part where they put other current liabilities.

Deferred revenue: Deferred revenue is payments that the company has received despite having not provided their product/services yet.

Commercial paper: Commercial paper is a debt instrument that is usually used when a company borrows money to fund short-term obligations like salaries, inventories, and the like.

Term debt: This refers to the loan that the company will have to pay.

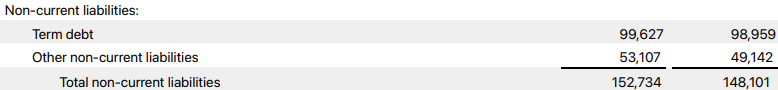

Non-current:

Non-current liability refers to the liability that a company has over the long term. This usually includes long-term loans and deferred tax (the tax that they will pay over the next financial year). Sometimes it can also include provisions (allocation for employees’ benefits).

From the example above, Apple only divided its non-current liabilities into two categories:

Term debt: the amount of debt incurred by Apple that it will have to handle in the next financial year.

Other: Well… it’s all the other liabilities that Apple decides they want to jumble up together.

Commitments & contingencies:

Commitments and contingencies here is interesting because it shows no value. This is a prerequisite in a balance sheet, but the value will usually not be shown. It’s usually just put there with an indication that the details will be explained in notes following the financial statement.

Commitments refer to any contractual obligations that the company undertook to any external parties. Contingencies are a company’s obligations that will only happen based on whether something happens or not in the future.

An example of contingencies, Company ABC is an I.T. Chinese firm that operates in the U.S. Suddenly, there are rumors that the U.S. will ban any Chinese I.T. business from operating there, Company ABC will now have to come up with a contingency plan to relocate their business just in case the rumor turns out to be true.

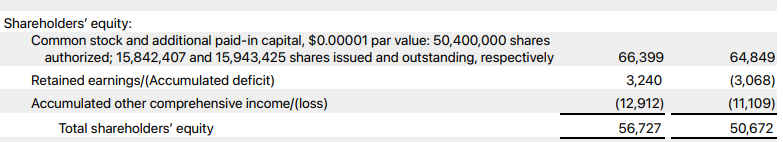

Shareholders’ equity:

Shareholders’ equity here is a part where the company sees how much they allocate for the shareholders. It’s there in the balance sheet to sort of tell “hey shareholders, this is how much money we have left if we use our assets to pay our liabilities,” if it looks good, investors will swarm for it.

The formula for Shareholders’ equity = Assets — Liabilities

Under this, there are a few things mentioned:

Common stock and additional paid-in capital: It tells you how much money the company makes from its investors, i.e., how much its shares are worth.

Retained earnings: It tells you how much money is left from the company’s earnings after they have paid their dividends.

Accumulated other comprehensive income (or loss): Refers to unrealized profit or losses from items that are placed in the “other comprehensive income’ category. This is honestly just some accounting stuff, and you wouldn’t need to know the details of why is it placed like this. All you need is just to look at the total shareholder’s equity.

Additional information:

- For an account to be balanced, the asset must be the same value as the liability plus shareholders’ equity; Total Asset = Total liabilities + shareholders’ equity.

- Why are they the same? It’s actually some accounting thing because the balance sheet is to see the balance in the account. A company’s source of finance is either equity or liability (such as getting funds from shareholders or getting loans). So, any asset that a company has essentially come from these two sources. That’s why Total Asset = Total liabilities + shareholders’ equity.

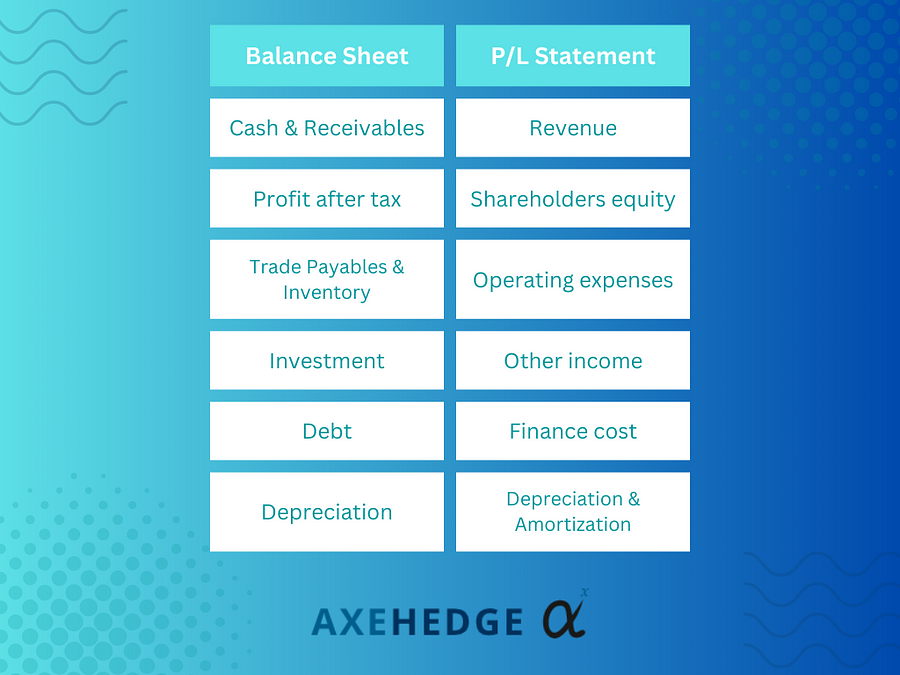

- Balance sheet can be interlinked with P/L statement so that you don’t get confused with so many terms because most of these are referring to the same thing, it’s just the technical terms are different. Below are how they can be linked:

Also read: Financial Statement: How to read a Profit & Loss Statement

Bottom line

- he whole point of a balance sheet is for you to see how much assets and liabilities the company is shouldering.

- Balance sheet can be divided into three parts: assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity.

- Division of assets and liabilities are: current and non-current.

- You can also get a general sense of how much the company is putting into its assets and future growth from the balance sheet.

Do keep an eye out for our posts by subscribing to our channel and social media.

None of the material above or on our website is to be construed as a solicitation, recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument. Investors should carefully consider if the security and/or product is suitable for them in view of their entire investment portfolio. All investing involves risks, including the possible loss of money invested, and past performance does not guarantee future performance.